There are basically two conditions that influence the creation of any work of art: they are: 1. the “inner” conditions including the skills, eye, hand and creative spirit and even life-style of the potter and 2. the “outer” conditions that lie beyond the potter. These include: not only the clay, wheel, tools, kiln and firing conditions but also the process of preparing the clay, the studio as well as the environment and atmosphere under which the potter works.

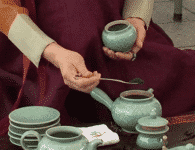

The potter brings to his work a working attitude. The old Korean potter had “han” a universal Korean spirit that I will leave to others to explain. He was most likely “jang-in” a master and/or he was “janggi” a free spirit. He just made the work. (In those days most likely the one forming the work was “he” a man [1]). He wasn’t encumbered by any attempt to be creative – just make the work — as many of the same pieces as one can make in a morning. Today there are Korean tea ware potters who can form on a wheel 400 tea bowls in the morning and trim them in the afternoon. So certainly a similar number was possible 600 years ago. But even if they only made 200 pieces, a lot of work was produced and not much time was spent on any of them.

Having worked with a very disciplined Japanese potter Inoue Manji, I have some sense of what is needed to produce a lot of the same pieces one after another in a short period of time. But I don’t think the Korean potter approached his work in the same manner as the Arita porcelain Intangible treasure Inoue. The Korean potter was relaxed, unassuming and approached his work with little or no thought. Those of us who have ever been “production potters” know that when you get “into the grove” of production work, your mind empties and your “body knowledge” simply take over. If we don’t care if they are perfect matches to one another the work produced is relaxed and natural. This process sounds very easy – just do it – but the reality of it is much different. We contemporary potters or “ceramic artists” have so many things that influence us that it is difficult if not impossible to adopt a “no mind”, or in Korean a “mot shim” approach. Hamada once told us, “It is nearly impossible to create loose work in a tight society.” We in the West have that problem. Hamada said that Japan suffers from the same problem – potters in a tight society attempting to create loose work.

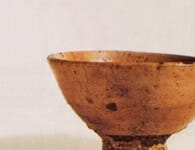

For the Korean Choson dynasty potter, making the “loose” bowl was natural, a result of the life and conditions under which he worked.

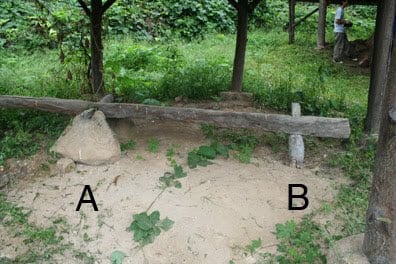

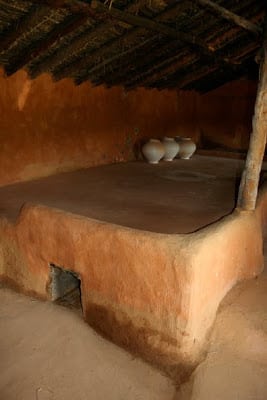

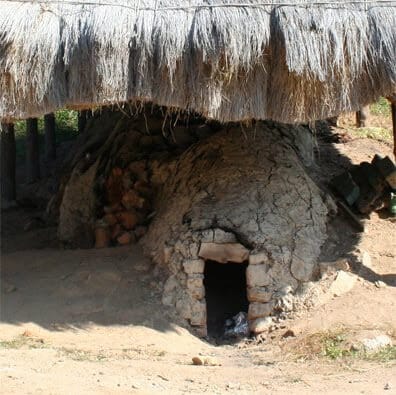

As in the studio above, the space for the studio might have been dug out of a hillside. This provided additional insulation for the studio. The walls of the studio might have been made of stones and raw clay and it probably had a rice straw thatched roof.

The wheel was a simple kick wheel with very little “carry” or centrifugal force. It might wobble slightly, a condition the potter thought nothing of. Forming on such a wheel, even one that does not wobble, is a challenge for Western potters who are comfortable with their electric wheels. But it was easy for the Korean potter who knew nothing else. A wobbly pot stops wobbling when the wheel stops – so it doesn’t matter.

Note: that some contemporary Korean tea ware potters choose to work with this type wheel today because of the special quality it gives to their work.

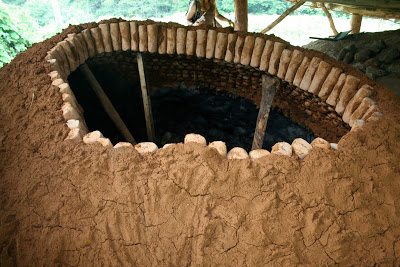

This old studio and its kiln could have been made at least 600 years ago and might be quite similar to the studio used by the potter who made the Kizaemon Ido tea bowl.

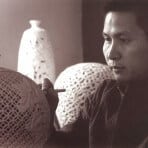

This studio is the family studio of the Kim family and is one of the only historically preserved studios in Korea. The father, grandfather and earlier generations of the Kim family used this studio. Kim Jong Ok, Korea’s National Intangible Treasure in ceramics, his son Kim Kyeong Sik and his nephew the potter Kim Young Sik are members of that family. The studio and kiln are in the care of Kim Young Sik. Their studios are in Mungyeong, Korea’s 1000 year old tea bowl village.

If the clay body was too dark (as in the case of the Kizaemon) the bowl was dipped into a whitish slip composed of a porcelain type clay and feldspar or ash. If that didn’t adhere well or the clay absorbed too much water from the slip and collapsed, the slip was brushed on using a rough brush (wait for a future post on buncheong). Everything was very natural and direct. After all of this, it was not uncommon for the potter to lose 50% or more of the work produced. Many potters today keep even less than this percentage of their work for exhibit and sale.

To fully understand this potter, we have to also identify with his life style. Such a description would take too long for this blog, but a quote from Hamada Shoji begins to explain it:

I think there are hardly any pots in the world through which a people’s life breathes more directly as Korean ones, especially Yi dynasty wares. Between pots and life, Japanese ones have “taste”, Toft wares have “enjoyment”, even the Sung pots have “beauty”, and so on. But the Yi dynasty pots have nothing in between; peoples’ lives are directly behind the pots.[3] From Hamada Potter by Bernard Leach, Kodansha International

The early Korean potter lived a life close to nature and his work reflected this natural connection. Your comments are welcome.

Footnotes:

[1] During the Chosun or Yi dynasty, women and children also worked in the pottery preparing clay and decorating. Today there are many well-established women ceramic artists in Korea and in modern Korea it was Ewah Woman’s University that first offered a class in ceramics.

[2] If the clay did not support such treatment, as trimming, the bottom would be beaten to compress it and if a foot were needed it would be wheel formed. This was a rare practice but potters adapted naturally to the type of clay they had. I may look at their tools in a later post.

[3] The term Yi dynasty was often used by the Japanese in reference to the Choson or Joseon dynasty. The Yi family ruled Korea throughout the length of the dynasty. Yi is sometimes also Anglicized as Lee, Rhee or Ri. Hamada was not referring to the “greatness” of the work in this statement but to the connection between a people and their work. However, it is evident from his many comments about Korean ceramics that it was greatly admired. It is well known that Korean work influenced Hamada Shoji’s work. In the first World Ceramic Exposition held in Icheon, South Korea in 2001 a special display showing the influence of Korean ceramics on the work of Hamada Shoji was featured. That exposition is held in three cities including also Yeoju and Kwangju. Are you interested in seeing this studio and kiln in person or in attending the next Mungyeong Teabowl Festival or the World Ceramic Exposition in Korea contact us to make that happen.

No comments