In a single moment he was dead, a victim of seppuku. Nothing could have prevented it; not the pleadings of Hideyoshi’s wife and daughter, not the intercession of samurai generals and Tea masters alike – nothing.

In preparation for this post I Googled “Sen Rikyu” and found 133,000 entries. (Now in 2013 there are 204,000) What more can be said? I am certainly not an expert on Sen Rikyu, but because he is near the heart of some of those aspects of Tea that interest me most. I have been reading about him and Toyotomi Hideyoshi for many years. To me, the ramifications that followed the death of Sen no Rikyu and their connection to Korea make that instant a key moment in teabowl history.

It is also interesting that of all the things written about Sen no Rikyu, one thing seems to puzzle writers most. Why did Toyotomi Hideyoshi command Sen Rikyu, this great man of Tea, to commit ritual suicide? In 1989, Japan made a movie to explore this question. The movie, Sen No Rikyu: The Death of a Tea Master, was highly rated but the question remains. (The movie is available on the web for a price.)

On the 28th day of the 2nd month of 1591 at his residence in Jurakudai, the palace he had helped to build, Sen no Rikyu wrote the following poem, raised his sword and carried out the command.

A life of seventy years,

strength spent to the very last.

With this my jeweled sword,

I kill both patriarchs and buddhas.

I yet carry one article I had gained,

the long sword and now at this moment

I hurl it to the heavens

A Biography of Sen Rikyu, Murai

There are other dissimilar translations. Two follow:

Welcome to thee,

O sword of eternity!

Through Buddha

And through Daruma alike

Thou hast cleft thy way.

Japanese Tea Ceremony. net

I raise the sword,

This sword of mine,

Long in my possession

The time is come at last.

Skyward I throw it up!

translation: Suzuki Dasetsu

A full ceremonial seppuku always has a death poem. (jisei no ku 辞世の句). That there are at least three different translations of Sen no Rikyu’s death poem underscores the confusion surrounding his death.

Many have speculated as to why Toyotomi Hideyoshi ordered Sen no Rikyu to commit seppuku (切腹). You may also be wondering why a blog on teabowls, such as this, would deal with such an issue.

Why did I, on this April day 2010, decide to address this morbid issue and post this blog on Sen Rikyu? I certainly do not enjoy morose thoughts.

I chose Sen no Rikyu because, particularly in the Western world, we cannot think about Teabowls without thinking about the contributions of Sen Rikyu. April is the month of Sen Rikyu’s birth – April 21, 1581. Of course that may be the Chinese calendar.

The death of Sen no Rikyu has intrigued me for years, not because I enjoyed the topic, but because, in my mind, seeking the answer to the question, “Why?” and the aftermath of the deed, are keys to understanding the influence of Korea on Japanese teabowls and indeed Japanese ceramics in general.

So why did the most powerful man in Japan the great Taiko ask his beloved tea master to commit seppuku?

There are many possible reasons. I come to the following possibilities because they have been “collecting” over the years from readings, and discussions with Zen scholars of Japanese history and other learned people.

Was it because a statue of Sen no Rikyu had been placed on the second floor of an important building above Hideyoshi’s statue that was on the first floor? Hideyoshi became so enraged that he ordered that building burned to the ground only for it to be saved by the suggestion that Sen Rikyu’s stature be removed instead. To burn it would have enraged too many others. Some think it was because Sen no Rikyu refused Hideyoshi’s request to take Rikyu’s daughter, the beautiful Lady Ogin, as a concubine. Perhaps it was because Lady Ogin had an unrequited love for Lord Ukon, who angered Hideyoshi by becoming a Christian convert. The movie Sen No Rikyu: The Death of a Tea Master suggests this as a possible answer. Hideyoshi, being Buddhist, reportedly did not like many Christians. However, after Sen Rikyu’s death he chose Furuta Oribe to be his tea master. Oribe was a Christian.

Sen no Rikyu strongly disapproved of Hideyoshi’s desire to invade Korea and China. Rikyu argued vigorously against this war and died a year before the invasion. Was that the reason?

Although Toyotomi Hideyoshi had been named Taiko – Absolute Ruler in the Emperor’s name – and thus achieved unparallel military power throughout Japan, he had always suffered because of his personal physical appearance. In addition Hideyoshi could never fully deny his own humble beginnings. Not being of noble birth, Hideyoshi could never be what he truly wanted – to be Shogun. Short and thin, Hideyoshi’s sunken features were likened to that of a monkey. Oda Nobunaga, a great warrior, but less than tactful man (for whom Sen no Rikyu was tea master before Hideyoshi), often called Toyotomi little Saru (monkey) and the ‘bald rat’. That would have surely bothered Hideyoshi. Finally there was the rumor some Japanese scholars say was true. Hideyoshi had syphilis of the brain and was slowly going insane. You may not read the latter reason in many accounts, certainly not Japanese ones, but a leading unbiased Japanese scholar told me this personally. Clearly, Hideyoshi had become jealous of his once beloved advisor and confidant. After all Hideyoshi was Taiko. Sen no Rikyu was merely a Tea master. Hideyoshi should receive all the accolades, love and praise.

Sen no Rikyu by contrast was beloved by all who knew him, at peace with himself, had achieved his life goals and was a true man of Zen and of Zen Tea. Even with great power, how can you really compete with that? Are these all not reasons for Hideyoshi, particularly if he was going insane, to command Sen no Rikyu to commit seppuku?

Ironically it took place at Jurakudai – the Palace of Pleasure that Sen no Rikyu helped to build. There was no pleasure in the palace that day – not even for Hideyoshi. He regretted his command.

As stated earlier, I begin to write about the great tea master Sen no Rikyu at the end of his life because, frankly, so much has already been written about Sen no Rikyu that there is little to add. Knowledge of how he died helps to clarify for me a great deal in the history of tea bowls. But unfortunately much remains unclear.

I will go back in history a few years in Sen Rikyu’s life and tell a story that I have also researched for many years. You may already know some or even this entire story or you may have never heard it. In any case it demands retelling – even if it too will remain confusing.

Allow me to set the stage. For part of this story Oda Nobunaga is alive and Sen no Rikyu is his tea master. I have already mentioned that after the death of Oda Nobunaga, under whom Sen no Rikyu was tea master, Sen no Rikyu became tea master for Toyotomi Hideyoshi. In 1586 Hideyoshi began construction of Jurakudai – the Palace of Pleasure. As part of the building process Hideyoshi asked Sen no Rikyu to purchase roof tiles for the palace.

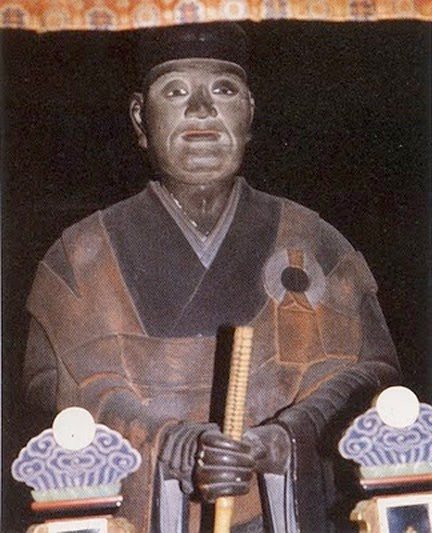

To do this, Sen no Rikyu visited the family of his old friends Ameya the rooftile maker and potter and Teirin, Ameya’s wife, who worked at his side. Sen no Rikyu had met them earlier when he was tea master for Oda Nobunage and had brought some attention to their work. Ameya, who had been called Sokei or Masakichi, was a Korean who immigrated to Japan around 1520 and married Teirin. On Sokei’s (Ameya’s) death (about 1560), Teirin became a nun and changed her style of work to Ama-yaki or nun’s ware. Chojiro and Jokei, their two sons, worked with her. Chojiro was already a potter and rooftile maker of some renown.

One account says that Sen no Rikyu had actually given Sokei and Teirin his old family name “Tanaka” after Rikyu had changed his name to “Sen”. Another account says that Rikyu’s family name “Tanaka” was given to the two sons. In any case there was a close relationship between Sen no Rikyu and Chojiro.

The name Sen, that Rikyu adopted, came from his grandfather Sen-Ami. Sen-Ami was also a Korean immigrant married to a Japanese lady. This made Sen no Rikyu ¼ Korean. Sen-Ami, Rikyu’s grandfather, was an aesthete working for Ashikaga Yoshimasa a local waolord. Various scholars speculate that some of the more natural teachings of Sen Rikyu’s aesthetics came from his Korean grandfather since they are almost identical to many earlier Korean aesthetic principals.

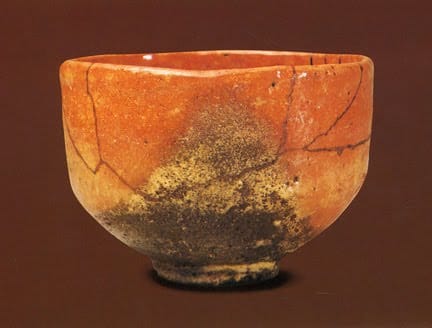

You may know that Sen no Rikyu commissioned Chojiro to make teabowls. Formed by hand with a simple glaze, these bowls had a natural feel and suited wabi-cha well. For many years these bowls were known as ima-yaki “now ware” since they were pulled from the kiln immediately after the glaze matured. Some even referred to these teabowls as Hasami-yaki or (tongs ware) since tongs were used in the firing process. This ware was so loved by the palace and by Hideyoshi that Chojiro’s bowls could not be sold to the general public.

After Chojiro’s death in 1589, Toyotomi Hideyoshi was so saddened and moved that he presented the brother Jokei with a seal on which was the word RAKU meaning “pleasure”. The word was derived from the name of the palace Jurakudai. The same place where Rikyu was ordered to commit seppuku. This is the same palace for which Sen no Rikyu bought roof tiles from Chojiro.

I wonder if Sen no Rikyu knew that Hideyoshi would have the roof tiles covered with gold leaf? Sen no Rikyu and Hideyoshi often had different aesthetic tastes – Hideyoshi more extravagant and Rikyu more humble.

The Tanaka family was so touched by the gift of this RAKU seal from the great Taiko that they changed their family name to Raku. That family became the Raku family dynasty that continues today in Kyoto, Japan. There they continue to produce Raku teabowls after fifteen generations.

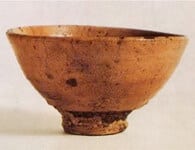

This Raku bowl is by Chojiro. Since none of Chojiro’s bowls were available for purchase by the public. It is highly likely that Sen no Rikyu used this bowl perhaps while serving Tea to Hideyoshi. The bowl is a great example of Chojiro’s work and the aesthetics of Sen Rikyu’s wabi-cha. Formed by hand and glazed with a simple transparent glaze there is a softness to the feel of this and all Raku bowls that suits them well to Tea.

Since not all of Chojiro’s red bowls have smoke marking, it is presumed that such markings may have initially occurred accidentally after the bowl was withdrawn from the kiln, while the glaze was still molten, and placed on some wood or brush that happened to be on the ground nearby. To quote from the Raku Family web site:

The form achieved in his tea bowls is a manifestation of spirituality, reflecting most directly the ideals of wabi advocated by Sen no Rikyu as much as the philosophy of Zen, Buddhism and Taoism. Chojiro, through his negation of movement, decoration and variation of form, went beyond the boundaries of individualistic expression and elevated the teabowl into a spiritual abstraction and an intensified presence.

Sen Rikyu, in life, helped to give birth to the humble tea bowls we know today as Raku.

On Sen Rikyu’s death, no one remained to argue with Hideyoshi against the invasion of Korea and the devastating Imjin War (Bunroku no eki). That war led to the death of approximately 3,000,000 people in Korea. Far more lives were lost than in any modern war. The stories of that war are horrific beyond comprehension. The war led to the dislocation of somewhere between 60,000 and 90,000 people of all types, men, women, children, scholars, poets and craftspeople of all types including an estimated 2000 potters who set up studios for many warlords in Japan. In the process the Korean potters founded numerous pottery villages. Many of those villages remain in Japan today. In a strange twist of fate it is possible to argue that had Sen no Rikyu not died and had been able to persuade Hideyoshi to not attempt to conquer Korea and China the face of both Korean and Japanese ceramics and specifically tea bowls, would be vastly different today.

Originally I was going to post this on April 1st but decided to postpone it a few days because of the odd significance of that day in the USA – perhaps beyond. I decided to look once more at the official Raku Family website and discovered that they, on April 1, 2010, had drastically changed their web site from what it had been for many years. It was a joke on me. Even much of the information had changed. It is not my intent to disrespect those who choose the content of the official Raku Family website. After considerable thought and conscious searching, I decided to present on my post the information I have been collecting on this story for many years. It comes from several sources that have also been doing research on the subject.

Notably one source is now on line in the 1901 book Japan Its History Arts and Literature Vol VIII Keramic Art by Captain F. Brinkley. Much but not all of his information is confirmed by other authors. Please also compare his Raku family linage on page 36 Japan History with the official Raku site.

If you go to the new Raku Family website, you will not learn that they have any Korean roots. Rather, they report that their roots are part Chinese and discuss evidence to prove it. For many years it has been the practice for Japanese people to deny the influence of Korea on their culture and/or that they might be themselves part Korean. One scholar told me that this practice is like denying the influence of African Americans on Jazz, particularly in the area of ceramics.

Was Chojiro part Korean or part Chinese? Were Chojiro and Jokei actually brothers? Did Sen no Rikyu give his family name Tanaka to Ameya or to Chojiro or not at all? (Just a few years ago Koreans who lived in Japan and did not change their name to a Japanese name could not own property – even if their family had lived in Japan for centuries.) In the final analysis, none of the facts of my post really matter. What we can agree on is the importance of the relationship of Sen no Rikyu to Chjiro and Jokei and the birth of a tea bowl that became Raku.

This is simply a blog. It is not a doctorial dissertation nor is it a book, both of which should require much more documentation. It was originally written to help clarify some things in my own mind about Sen Rikyu’s death and the impact on Korean and Japanese tea bowls – not to confuse the history of Raku. After all the real purpose of this blog is simply to think about and enjoy some teabowls.

A Note:

The term “Raku” should not be confused with the Western ware inspired by Raku and developed principally by Paul Soldner that we know as “raku”. After watching Paul Soldner demonstrate his process, the great teabowl master Raku Kakunyu XIV spoke with Soldner and said , “It is an interesting process but it is not Raku. I am Raku.” This story came directly from Paul.

An Addendum Bowl:

While the above Chojiro Raku teabowl is truly a great one. it is not the the bowl that first inspired me to think about writing about Sen Rikyu. That bowl was a Korean Goryeo Dynasty celadon bowl that I did not include in my last post. This celadon bowl was officially documented as having been used by Sen Rikyu. Japan keeps very extensive records on official tea ceremonies. Reportedly Korean bowls were used the majority of the time.

Known as the Naniwazutsu, this celadon bowl is very different from those on my celadon teabowl post. First it is not an ‘open’ form but is upright. Celadon was made throughout Korea during the Goryeo Dynasty and although many of the “finest” celadon came from Gangjin it is immediately clear from the crackled glaze that this piece does not come from Gangjin. This bowl is too unrefined.

That is how it should be for a Sen no Rikyu bowl. Although Goryeo celadon is known for its sophistication. There is something about this Goryeo bowl that remains humble. Is it the slightly pock marked surface with its partially under-reduced tea stained crazed glaze or the innocently carved and inlaid ‘sang hwa mun‘ cranes, ironic symbols for long life – while Sen Rikyu’s life was shortened? Is it the simple stamped chrysanthemum a symbol for cheer and optimism – and an object for meditation? Or is it the off-center form that we know fits the hand perfectly?

The Naniwazutsu feels like a bowl that is for quiet personal contemplation and meditation, not a bowl to be shared. I wonder if Sen no Rikyu used it in that way?

It is also one of those rare chawan that seems like a cross between a chawan (teabowl) and yunomi (watercup) in Japanese. Many Western potters don’t seem to understand or ignore the difference. That is a topic for another post.

In any case, I hope you enjoyed this post. Your comments and suggestions are encouraged and welcome.

Special thanks to Alan Covell for permission to post the photos from his books and the insights those books have been giving me. Dr. Jon Carter Covell, Alan’s mother was a close friend. We miss her insights into Japanese and Korean culture greatly.

No comments